In May, now-ousted U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the start of the Trump Administration’s “zero tolerance” policy to separate migrant families at the Mexican border. “If you are smuggling a child” into the country, he said, “then we will prosecute you, and that child will be separated from you as required by law.” In just six weeks, more than 2,600 children were taken from their parents or other adults. Although a federal judge ordered the government to reunite all children with their families by July 26, hundreds likely still remain in U.S. custody. And the psychological trauma inflicted is likely to cause lifelong damage to these children, experts say.

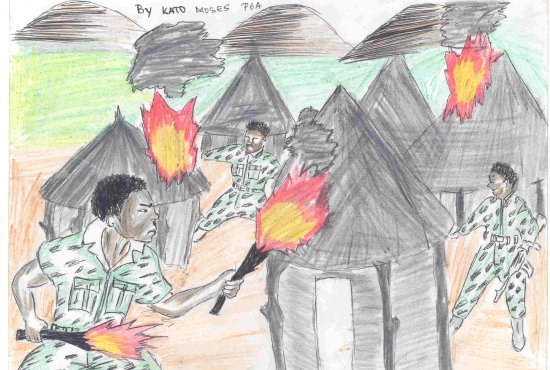

Figuring out how children themselves are responding to trauma tends to be particularly difficult, because they may not be able to communicate how they feel. For decades, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) has worked with tens of thousands of children in struggling, often war-torn nations around the world who are suffering from what’s called toxic stress — a relentless cycle of trauma, violence and instability, coupled with a lack of adequate care at home. In some cases, the IRC has used drawing to help children open up or as a way to process their trauma. The drawings here, from IRC projects in Cambodia during the genocide, in Sierra Leone and Uganda in the early-2000s and in Jordan just last year, show what it’s like to endure displacement, violence and separation, through the eyes of the children themselves.

“Across decades, children are expressing the trauma of violence in very similar ways,” says Sarah Smith, senior director of education at IRC. She says drawings like these show just how urgent it is to intervene and provide psychological and social support.

Stress falls into three categories. Positive stress is perhaps best understood as a personal challenge that you can deal with; it’s an essential part of healthy development, like a child spending their first day with a different caregiver. It can also be useful, like adrenaline making you think faster before giving a speech. Tolerable stress is a more difficult situation — like the loss of a loved one or a severe injury — that is buffered by a supportive relationship and can still prove beneficial. But toxic stress is insidious, paired with the fact that these buffering relationships are not there. For a child, that could be anything from chronic abuse in the home to grinding economic hardship — all without the protection of a loving adult.

But toxic stress is not a form of incurable dysfunction or damage. “It is a healthy biological response to an unhealthy set of circumstances,” says Smith.

That healthy response is what your body does when preparing itself to either confront or run away from a threat. The brain communicates with the body through the nervous system to trigger this fight-or-flight response: your heart rate and blood pressure briefly increase, and you start secreting stress hormones like cortisol.

“When the stress goes on for a long time, these changes gradually eat away at the body,” says Charles Nelson, a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital. Stress essentially shuts down the body so that it can survive, reverting to its most basic needs and relegating functions that it perceives aren’t for immediate survival. That ranges from executive functioning — the more complex calculating and planning ahead — to the capacity for empathy. When a child is living under a long period of toxic stress, the body doesn’t put effort into developing those higher-level functions. It’s also more difficult for them to regulate emotions.

Toxic stress can have long-term repercussions, affecting a child’s physical growth — slowing them down from putting on height and weight — and transforming their brain architecture. According to studies, children separated from their parents early in life and raised without a constant, loving caregiver suffer a profound impact on cognitive ability, social function, mental health and brain development. Adverse experiences in childhood increase the chance of health problems like heart disease, diabetes and substance abuse.

“There’s also an increased propensity to be involved in criminal activities, both as victim and perpetrator,” says Meghan Lopez, an adjunct professor at John Hopkins University and Head of Mission in El Salvador for the IRC. “When you look at the long-term profiles of children growing up with toxic stress who become adults, it sounds a bit like the gang members that we have in El Salvador.”

But breaking those patterns is entirely possible, especially with the help of a supportive community. “We do have to work with teens and help them build alternative paradigms,” she says. “But it’s perhaps even more imperative to work with children in the earliest years and work with their parents to learn new models of parenting.”

Stress spans generations in Honduras and El Salvador, the home nations of many of the estimated 2,000 migrant children in the approximately 5,000-person caravan heading toward the U.S.-Mexico border. “The parents have lived through wars, military dictatorship, hurricanes, earthquakes, and the current cycle of violence,” Lopez says. They may struggle to care for their children as a result. “The subtle and ongoing insults to resilience and wellbeing can be some of the most difficult things for asylum-seekers to prove. But they can be much more damaging.”

There’s not enough research yet to chart the broader societal impact when an entire generation or community undergoes toxic stress. But Nelson, who spent years working with abandoned children in Romania, worries about the kinds of subtly-entrenched messages kids pick up on in countries that have suffered years of conflict, like Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan. “Children are probably born inherently with a sense of wonderment, hope and curiosity, but it won’t take much to beat that out of them,” he says. “Imagine growing up in a culture where there’s no hope and there’s no resources. What you may be picking up on in these drawings is about how children express their mental view of their lives.”

What isn’t hopeless, however, is the task of helping children who have suffered toxic stress.

Studies have shown that some children are naturally more resilient than others, in part because of genetic differences. But resilience lies not just within the child but also in their environment, Nelson says. That means it can be found and promoted in lots of different ways.

“Even in the most dangerous neighborhoods in El Salvador, there are lots of families creating a safe space for their children,” Lopez says. What’s crucial, experts agree, is for a child to have a constant, caring and engaged adult in their life — ideally a parent but it could also be a grandparent, an aunt or uncle, a teacher, a nurse or a police officer. That can reduce the impact of toxic stress by as much as 50%, Lopez says.

Some argue children are also more resilient than adults because their brains are more malleable: the pathways and connections haven’t all been established, so it’s easier to make new ones. (For instance, it’s much easier to learn a new language as a child than as an adult.) But while it might be easier to bounce back from hardships when you’re younger, your sense of time and perspective is also altered and it’s tougher to determine what is a true threat to your life or wellbeing.

That’s why children need long-term interventions delivered by trained mental health professionals, experts say. Creating a safe environment and reassuring a child that they are safe, as well as tending to the parents’ mental health needs, are all paramount. “We can’t prevent war but we can prevent a lot of violence that happens in homes,” Smith says. “There are lots of techniques to help parents coping with their own stress so that they don’t resort to violent discipline.”

For children, evidence-backed approaches range from more universal ones — for kids who have been displaced or witnessed violence but aren’t showing symptoms — to more targeted ones for children suffering more severe repercussions. Mindfulness techniques, such as belly breathing and brain games — helping children practice concentration skills, for instance — have all helped children improve the skills most impaired by toxic stress. Larger-scale IRC programs in Congo, Pakistan and West Africa have indicated a positive impact for children’s learning outcomes and socio-emotional behavior.

“The body is amazing,” Lopez says. “It can almost always recover.” But in order to do so, a child needs the support to build their confidence again. That’s what makes separating families so dangerous, she says.

On Oct. 13, President Trump confirmed he was considering a new family separation policy, arguing it was an effective deterrent to illegal border crossings. “If they feel there will be separation, they won’t come,” he said. Humanitarian workers and analysts disagree. They say the individuals will not stop fleeing until the root causes of violence are tackled. “The children that are making their way to the border have already been living under toxic stress in their home countries,” says Lopez. “Their families have chosen to take this journey because there is no better option.”

Separation is not a solution, she maintains. “Taking away their parents is taking away the most powerful tool that can make a difference to children under toxic stress — and that’s a stable, loving, known caregiver.”