Giorgia Meloni's politics may be at odds with Biden's, but the two have found common ground over Ukraine, China, and more.

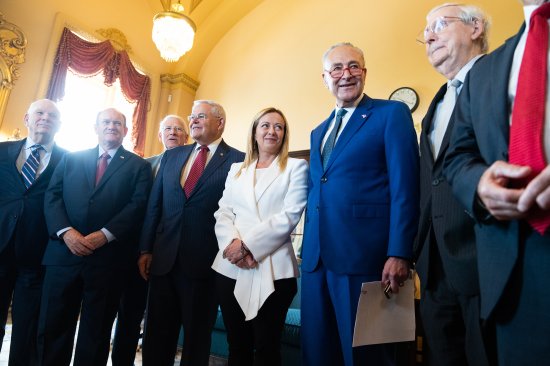

Getting an invitation to the White House is no easy feat (just ask Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu). But on Thursday, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni will join the relatively small band of leaders who have been welcomed to the Oval Office by President Joe Biden this year, among them Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, U.K. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, and South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol.

An invitation to the White House is historically commonplace for Italian leaders (Meloni’s recent predecessors Mario Draghi and Giuseppe Conte both received invitations from Biden and his predecessor Donald Trump, respectively). Still, that the President has chosen to welcome Meloni may nonetheless come as a surprise to observers given her far-right leanings and position as the head of a party with neo-fascist roots.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]But unlike her fellow hard-right nationalist leaders such as Hungary’s Viktor Orbán or Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Meloni is no international pariah, thanks in large part to strong position on the war in Ukraine. Since taking office in October, the Italian leader has largely exceeded Western expectations and has even invited praise for her strong Atlanticist positions. During a visit to Britain in April, Sunak paid tribute to Meloni for her stewardship of Italy’s economy and her leadership on Ukraine, noting that the values between their two countries are “very aligned.” The following month at the G7 summit in Hiroshima, Meloni was pictured holding Biden’s hand.

This kind of embrace might have been unthinkable just 10 months ago, when Meloni’s victory was widely regarded as a harbinger for democratic backsliding in Italy and beyond. (Even Biden shared this trepidation, citing her victory as a warning to Democrats, noting that “we can’t be sanguine about what’s happening here either.”) But Meloni’s acceptance on the international stage, by the U.S. and others, has largely been based on shared priorities in the foreign policy realm. On Ukraine, Meloni has proven herself to be a stalwart NATO ally and a staunch proponent of increasing military aid to Kyiv, despite just 39% of Italians agreeing. Responding to a fellow lawmaker who suggested that Italy halt its support for Ukraine, Meloni said: “If we stop, we allow the invasion of Ukraine. I’m not hypocritical enough to mistake an invasion with the word ‘peace.’”

More From TIME

In Meloni, Biden will not only see a partner in facing an assertive Russia, but also a rising China. Indeed, one of the main topics of focus in their meeting is likely to be Italy’s contentious membership in China’s Belt and Road Initiative—Xi Jingping’s flagship infrastructure scheme, known as the BRI—which is up for renewal in December. While Meloni has previously called Italy’s involvement in BRI “a big mistake” and there have been suggestions that she favors pulling Rome out of the deal, she has yet to make a formal decision. Luigi Di Gregorio, a professor of political science at Tuscia University, tells TIME that a public announcement during the visit is unlikely as there are “many interests at stake” and Meloni will want to avoid provoking retaliation from Beijing.

This doesn’t mean that Biden won’t raise the issue, though. “In the United States, the U.S.-China relationship and the U.S.-China competition is basically what colors most of our foreign policy and a lot of our domestic policy as well,” says Rachel Rizzo, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center, citing the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act as recent examples of Washington’s efforts to revitalize American manufacturing in a bid to better compete with Beijing. “Biden is going to use this opportunity to try to push Italy in the direction of not renewing it.”

Among the other topics that are likely to come up over the course of Meloni’s visit is Italy’s upcoming G7 presidency next year, as well as her recent efforts to curb migrant flows across the Mediterranean and transform Italy into a major energy hub as Europe seeks to wean itself off Russian gas.

But foreign affairs is where Biden and Meloni’s commonalities end. Domestically, the Italian leader has pursued an agenda that is largely in keeping with her party’s socially conservative and nationalist ethos. Since coming to power, her government has continued its vilification of the LGBTQ+ community, even going so far as to pursue a crackdown on same-sex parents. They have also put their anti-migrant views into practice, most notably by refusing to offer a safe port to a boat carrying roughly 230 people, a quarter of them children. (However, Meloni recently announced that Italy would be open to creating more legal paths to the country, as “Europe and Italy need migration.”) Meloni’s policies have also been seen to be at odds with Rome’s international climate commitments.

Ideological differences notwithstanding, this White House meeting represents an important opportunity for Meloni—one that could solidify her position among Western leaders as an important and equal partner on the international stage. One of Meloni’s main asks of Biden, according to Bloomberg, will be for Italy to be treated on par with France and Germany, having previously felt excluded when, during last month’s attempted Wagner mutiny in Russia, Biden held calls only with Paris, Berlin, and London.

“She probably wants to send a message that the Italian right isn’t just Italian—it’s representative of broader movements throughout Europe,” says Rizzo, noting sustained support for far-right parties in Germany, France, and Spain. “She wants to lend credence to the right-wing movements throughout Europe, writ large, not just in Italy itself. And she does that by saying, ‘Focus on what we do on the international stage. … [And] look the other way on what we’re doing domestically.’”