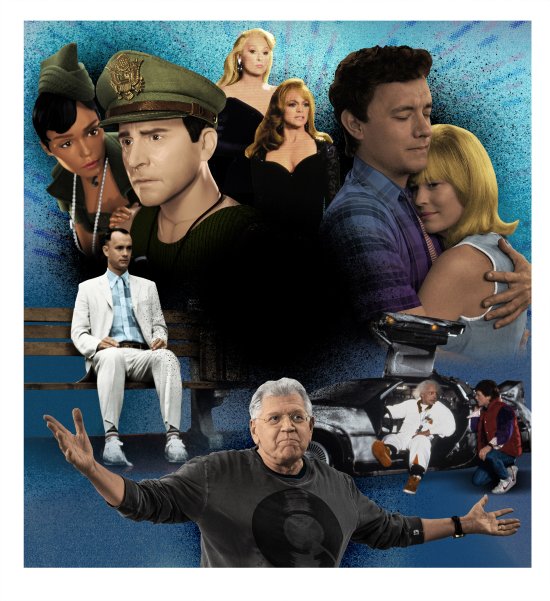

The famed director on his new movie 'Here,' starring Tom Hanks and Robin Wright, and his views on AI, sentimentality, and originality in Hollywood today.

Robert Zemeckis’ Here is the most unfashionable movie of 2024—which is exactly what’s beautiful about it. In a world where even those who profess to love movies largely stream them at home, Here is a picture that demands big-screen real estate. It’s inventive and confident filmmaking from a veteran director whose most recent features have performed modestly at the box office or, worse, sunk with barely a trace. It’s so unabashed in its desire to make us feel something that it runs the risk of being called sentimental—some early reviews have labeled it as such. It’s the kind of movie that a whole family—from young teenagers to nonagenarians—could trek out to see on a Sunday or holiday. And it reunites two stars—Tom Hanks and Robin Wright—who helped make Zemeckis’ 1994 Forrest Gump such a resonant success.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]In 2024, all these pluses are almost minuses, relics of things we no longer look for in movies. But Zemeckis—who, in a career spanning more than 40 years, has hit some high highs and a few rather low lows—is optimistic that audiences will find their way to Here, not just because he wholeheartedly believes in it, but because he knows it’s a miracle it got made in the first place. “It defies everything that’s happening in the corporate whatever,” he says in a Zoom call from Los Angeles, “[among] whoever it is that makes decisions about what movies should be made.” Maybe because his last film to receive a traditional theatrical release, 2018’s tender, innovative, and mildly strange Welcome to Marwen, failed to find an audience, he knows a miracle when he sees one. “Hey, the truth is that I could never make any of the movies I made, today. Not a single one.” Why? “Because,” he says, with deadpan understated confidence, “they’re too original.”

Maybe that sounds like hubris. But for someone who knows, provably, how to connect with moviegoers in an actual theater—as he did with Forrest Gump, with Back to the Future and its sequels, with pictures like Cast Away and Who Framed Roger Rabbit—it’s really just a reckoning with the state of moviegoing today. Most of us watch movies in isolation, which Zemeckis sees as a huge problem. It’s easy to forget what it feels like to laugh as part of a larger audience of human beings, or to be part of a crowd of viewers who allow themselves to be swept along in a wave of emotion. And though we think we want to see something original, do we really? If so, the mountains of product being made from already-familiar IP means we’re out of luck.

What chance does a movie like Here have in a world like that? Zemeckis, more than anything, sounds grateful that he’ll have a chance to find out.

Read more: The 100 Best Movies of the Past 10 Decades

Adapted from Richard McGuire’s 2014 graphic novel, a landmark for its visual inventiveness, Here—set in a single room of one house, and covering centuries’ worth of life in that exact location—is, from a technical standpoint, unlike any other film ever made. The camera is stationary, as it used to be in the days of silent film. But in Here, that stillness feels exhilarating and modern, given that what we see within the frame moves and changes not just with passing days, years, and decades, but with eons. We see a young couple enter this room—the Second World War has just ended, and these two are looking forward to building a life together. But we’ve also seen the ground on which this house was built as an early home to dinosaurs (who trample over a couple of prehistoric eggs as they valiantly try to outrun death) and later to North America’s indigenous peoples, who fall in love and build families just as our post-World War II couple will do (though they’re not nearly as fully fleshed out as characters). Across centuries the landscape shifts from barren earth to verdant, flowering fields—the story flashes backward and forward in time, though it never leaves this relatively small patch of space. Within this single frame, small interior squares pop up to show what was happening in this exact spot decades ago, or what might happen in a few decades’ time.

From the minute Zemeckis picked up McGuire’s novel, he saw it as a film. But getting the result he wanted wasn’t easy, not even for a filmmaker known for his fluency in special effects. “When I started getting my team together and described the style of the movie I was going to make, everyone’s reaction was ‘Well, that won’t be a problem.’ And it turned out to be maybe the most difficult movie we ever made,” Zemeckis says, “a gigantic puzzle.”

Nestled within that puzzle is the story’s heartbeat. Our postwar couple, Al and Rose, are played by Paul Bettany and Kelly Reilly. They give birth to a son, Richard, who, from his teenage years to old age, is played by Tom Hanks. While he’s still in high school, Richard meets and falls in love with Robin Wright’s Margaret. She gets pregnant; the two marry, living with Al and Rose ostensibly only until they can afford a place of their own, though that day never comes. The extended family lives under one roof, and not always happily. There are births, deaths, major illnesses, and marital frustrations. Wright and Hanks anchor the film’s drama, and to play the younger and older versions of their characters, their faces and bodies are enhanced digitally.

The de-aged versions of Hanks and Wright are admittedly a little disorienting, especially at first. But Zemeckis—who, with films like The Polar Express (2004) and Beowulf (2007), has long been a proponent of performance-capture and other digitally advanced technologies—bristles at the suggestion that audiences might think of Hanks and Wright’s appearance as “uncanny.” He hates that word. The only reason people might have that response, he says, is because they know they’re seeing a movie illusion. He explains that the effect is nothing more than digital makeup; he finds the results perfect, and perfectly believable, given how much de-aging technology has improved since Martin Scorsese used it in The Irishman, in 2019. (The de-aging in Here was accomplished via an AI technology known as Metaphysic Live.)

But when pressed to acknowledge that some viewers might find that very perfection unsettling, Zemeckis concedes that the effect might require a small leap of imagination. “It’s an intellectual exercise,” he says. “An audience might be going, ‘Oh, how can that be? I know they’re not that age.’” But test audiences, he says, weren’t overly bothered. “They quickly got over it.” And while he acknowledges that unchecked AI presents a danger to actors’ livelihoods, he considers the technology used in Here to be completely defensible from an artistic standpoint. “AI is a catch-all phrase, because what I’m doing is just using really fast computing to create digital makeup. I’m not creating any kind of avatar or anything.”

In the end, Zemeckis might be right that the sight of a “young” Hanks and Wright, reunited after 30 years, may be enchanting enough to carry audiences along. Yet not even Forrest Gump can escape the scrutiny of audiences who feel they’re too sophisticated for it: for every person who remembers the movie with pleasure, there’s one who derides it for its ostensible schmaltziness. It seems the only thing the latter group can recall about the film is the sugary bromide about life being just like a box of chocolates; they don’t care how beautifully crafted, and acted, it is, and its sly humor—which you’d think would be self-evident in a story about a naïf trying to make sense of 20th century history—seems to have totally slipped past them.

Zemeckis has some ideas about why modern audiences, especially, have issues with Forrest Gump. “I think modern audiences have lost the understanding of irony because they watch a movie like Forrest Gump in isolation, and they don’t understand the irony of what it was, what it’s all about. They take it a hundred percent literally,” he says. “And filmmakers like me, who find irony in life and in art and in movies—that’s getting lost somehow.” Still, there’s hope. Zemeckis’ bitterly funny 1992 satire Death Becomes Her, considered a flop upon its release, has been rediscovered and embraced by younger audiences. Both it and Back to the Future have also been reimagined as Broadway musicals; their bones are enduring.

Read more: The 33 Most Anticipated Movies of Fall 2024

Perhaps, whether it’s an immediate hit or not, Here will have a similar shelf life. The movie captures the sense that time seems to stretch before us endlessly when we’re young; it’s only when we stop and look back that we realize time isn’t our own, to use or control. The spaces we fill today were filled by others before us, and will be filled by someone else tomorrow—though another way of looking at it is that all beings are interconnected across dimensions. Common experiences unite us: Our parents fall ill or simply age, and we must care for them. Babies are born at inconvenient times, but we make it work. People we love leave us behind. Our children grow up to live their own lives. At one time or another, we all ask the same question: Where did the time go?

The dazzling construction of Here gets at the unanswerability of that question. There’s something searching and wistful about this movie; it couldn’t have been made by a young person. In adapting McGuire’s book, Zemeckis worked with his frequent collaborator (and Forrest Gump screenwriter) Eric Roth, and though the story stretches across centuries, it’s particularly affecting in the way it captures life in mid- to late-20th-century America. When Al brings out his home-movie camera, circa 1960, the family squints into the glare of the light bar necessary for shooting indoors: this is how midcentury parents captured our happiest moments, by nearly blinding us. The family TV in the corner hits the high points of each era (the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show) or at least nods at the weird stuff that gets stuck in our brains (the opening sequence of CHiPs).

But any film that tangles with big human feelings risks being characterized—to come back to that all-too-convenient word—as sentimental. Zemeckis is ready for that. “I think people who use the word sentimental just don’t like the fact that they were moved. It makes them scared, and I think they’re lashing out at a feeling that makes them uncomfortable.” Watching movies in isolation, removed from that ripple of communal feeling, has done us no favors. Maybe it’s time we relearned how to feel uncomfortable, together—to bring it back into fashion, before it goes extinct.