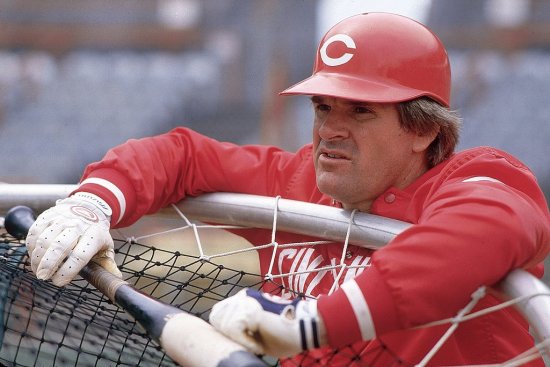

Rose became baseball’s all-time hit leader in 1985. Four years later he was banned from the sport for life for gambling.

LeBron James broke the NBA’s all-time scoring record back in February of 2023, surpassing Kareem Abdul-Jabbar on the all-time list: James now has 40,747 points and counting.

Imagine, less than a handful a years from now, LeBron was banned from basketball for life.

It’s ludicrous.

Lionel Messi has scored 841 goals for club and country, while captivating America with his exploits upon arrival in Miami last summer. He’s won a World Cup, a pair of Copa América’s and double-digit league championships.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Imagine that by 2028, Messi was gone from his game.

Also unimaginable. But for the generations who did not grow up in the era of Pete Rose, baseball’s all-time hits leader who died, at 83, on Monday, the Clark County (Nev.) Medical Examiner’s Officer confirmed to TIME, it’s perhaps some helpful perspective. Rose’s 1985 ascendance past Ty Cobb on the career hit list, at a time when baseball—much like basketball and soccer today—produced players and moments that permeated American culture, probably generated more awe and mass reflection than even James’ passing of Abdul-Jabbar in points.

Which made Rose’s downfall, due to a betting scandal that drove the news cycle—such as it was back in the summer of 1989—that much more monumental. Rose’s gambling got him banned from baseball for life that year. And despite so many fits and starts over the years, he never really got back in.

For years after the 1989 investigation that found that Rose, while playing for and managing the Cincinnati Reds, had placed bets on baseball, he denied ever doing so. He and former commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti signed a deal in which Rose agreed to the lifetime ban, in exchange for Major League Baseball declining to make a formal determination on whether or not he gambled on the game. Giamatti died on Sept. 1, 1989, a week after the deal was struck. Rose also spent five months in prison after pleading to tax evasion charges in 1990.

Rose finally admitted to betting on baseball as manager in his 2004 autobiography, though he denied ever betting against the Reds and manipulating the outcome of a game. But his lies ultimately kept him out of the Hall of Fame, still a sore spot for baseball fans who believe a player’s on-field accomplishments alone deserve recognition. In 2015, Rose made a request for reinstatement: MLB commissioner Rob Manfred turned him down, after Rose claimed he couldn’t remember investigative evidence pointing to his betting as a player in 1985 and 1986, years when Rose was a player-manager for the Reds. “Mr. Rose’s public and private comments … provide me with little confidence that he has a mature understanding of his wrongful conduct, that he has accepted full responsibility for it, or that he understands the damage he has caused,” Manfred wrote.

Betting was a cardinal sin in baseball ever since the Black Sox scandal of 1919, when Chicago White Sox players like “Shoeless” Joe Jackson were accused of fixing games in return for payments. Today, sports gambling pervades baseball and other leagues: FanDuel, for example, is an official sports betting partner of Major League Baseball. Yet, although American sport has embraced gambling, Rule 21 still holds in baseball: “Any player, umpire or club or league official or employee who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in connection with which the bettor has a duty to perform shall be declared permanently ineligible.” A fan can bet on baseball where it’s legal. A person in Rose’s position couldn’t do it then, and can’t now.

The last three-plus decades were a cruel final chapter for a man who breathed baseball. “I’d walk through hell in a gasoline suit to play baseball,” he once said. Growing up in Cincinnati, Rose had no backup plan: he was going to be a pro ballplayer. That he made it for his hometown team only added to his allure. Rose was the MLB Rookie of the Year in 1963 and he won three World Series titles, back-to-back championships with Cincinnati’s “Big Red Machine” in 1975-76 and another while playing first base for the Philadelphia Phillies in 1980. He played for 24 seasons, and is also baseball’s all-time leader in at-bats and games played.

During his 1973 MVP season, when he played left field for the Reds, Rose had a career-high 230 hits, and topped the National League with a .338 batting average. His aggressive style of play—the head first slides, the sprinting to first base on walks—earned him the nickname “Charlie Hustle.” He barrelled over Cleveland catcher Ray Fosse during a home-plate collision at the 1970 All-Star Game, separating and fracturing Fosse’s shoulder. No matter that the All-Star game was a meaningless exhibition. Rose never apologized to Fosse, whose career was never the same, for the incident.

Post-baseball, Rose made a living in Las Vegas signing autographs. News of his death broke around the time both the New York Mets and Atlanta Braves were celebrating clinching playoff spots, together, at Truist Park in Atlanta. New York’s thrilling 8-7 victory over Atlanta in the first game of a doubleheader, which needed to be played to make up games postponed due to Hurricane Helene last week, sent the Mets to the playoffs. Then the Braves won the second game, also securing a postseason spot.

It was a celebratory day for America’s pastime, saddened by the passing of an all-time great who, if not for stubbornness and sins, deserved a celebration of his own.