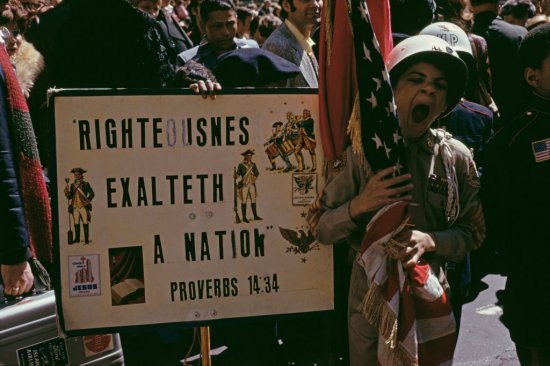

The Trump campaign is signaling that it intends to make the U.S. a "Christian nation." Here's what that idea looked like in history.

When speaking recently at an evangelical town hall led by Lance Wallnau, J.D. Vance explained that his goal of dramatically restricting U.S. immigration is grounded in the “Christian idea that you owe the strongest duty to your family.” His comments and appearance with the man who has in the past described himself as a Christian nationalist engages a set of beliefs common in the Republican Party and among a slice of the electorate: that America was founded as a white “Christian nation” based on God’s law as expressed in the Christian Bible.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Indeed, at a meeting of conservative Christians in February, Trump appeared to gesture toward that idea, with his promise that, “With your help and God’s grace, the great revival of America begins on November 5th.”

Despite this rhetoric, the U.S. was not founded as a “Christian nation,” an idea the Trump campaign rhetoric supports. Historically, laws at the state and national level during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, meant to counter waves of Catholic and Jewish migration and to suppress Black suffrage, sought to wed Protestant Christianity and white supremacy to the state. Such attempts led to widespread suffering, poverty, and death, especially for racial and religious minorities targeted as “immoral” by Christian activists.

Today we remember the product of this Christian nationalist movement as Jim Crow, the brutal and repressive set of laws and practices that structured American life from the 1890s through the 1960s. The terrible suffering they created shows that—if America was indeed a “Christian nation”—there is nothing less desirable or great than making it one again.

Following the abolition of slavery after the Civil War, white evangelicals embarked on a reform campaign, aiming to purge society of what they viewed as religious and social ills. They founded powerful advocacy organizations like the American Economic Association and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union to, in the words of one reformer, “bring to pass here a kingdom of righteousness.”

Read More: Trump’s Christian Nationalist Vision for America

Advocacy organizations like these sought to pass laws beginning in the 1890s criminalizing drinking, swearing, and loitering while working to restrict integrated spaces, immigration, voting, and reproductive rights. While these laws and organizations varied based on locality—the Asiatic Exclusion League in San Francisco targeted Asian Americans, for instance—the legal and organizational framework they created promoting white Christian power, at the expense of other groups, was national in scope.

Frances Willard was among the most prominent of these Christian reformers and longtime president of the national Women’s Christian Temperance Union. A northern daughter of abolitionists, her biographer noted that “she never let go of her belief that a healthy democracy required all its citizens to conform to a singular standard of morality.”

To achieve that end, Willard worked to ban the sale and consumption of alcohol while supporting the suppression of groups she found morally unfit. For example, during the Mississippi Constitution of 1890, convened specifically to formally disenfranchise Black voters, Willard touted its work as an example of moral reform and called for it to grant limited voting rights to white women while disenfranchising Black men. The convention failed to give the vote to women, but it used poll taxes and felon disenfranchisement to restrict Black suffrage. Often considered to be one of the foundational texts of Jim Crow, the new constitution framed its work as seeking to harmonize civic life with the divine, with the text “invoking His blessing on our work.”

Willard’s comments in support of Mississippi’s disenfranchisement convention were especially egregious because she made them amid public debate over lynching. After the Civil War, white conservatives had pioneered mass violence and intimidation tactics to prevent Black suffrage and undermine civil rights. The pervasiveness of these tactics and the inability of Black survivors to get justice from white police, public officials, and juries, led federal officials to consider legislation protecting those “whose votes are now suppressed under the pretense of maintaining race supremacy as against the negro.” It was against this measure and this backdrop of racial violence that Willard spoke out.

Willard viewed white Southern Christians’ resort to violence as understandable. “The problem on their hands is immeasurable,” she explained, because “the colored race multiplies like the locusts of Egypt.”

Lynching had become such “epidemic of mob law and persecution,” Frederick Douglass observed in 1894, that “it [was] no longer local, but national; no longer confined to the South, but has invaded the North.” Douglass argued that although lynch mobs subverted the judicial system, they also functioned as an extension of it because lynchers operated with tacit approval of local public and religious leaders.

Read More: Modern Far-Right Terrorism Is a Repeat of Reconstruction-Era Themes

This formalized lawlessness and its increasingly national scope, Douglass reasoned, undermined American religiosity. “We claim to be a Christian country,” he thundered, “and a highly civilized Nation, yet I fearlessly affirm that there is nothing in the history of savages to surpass the blood-chilling horrors and fiendish excesses perpetrated against the colored people by the so-called enlightened and Christian people of the South.”

Like Douglass, Willard saw the stakes of lynching for the idea of a Christian nation, but claimed that “a more thoroughly American population than the Christian people of the South does not exist.” For the white Christian nationalists of the Deep South, lynching represented less a rejection of Christian doctrine than its embrace within a fundamentalist context.

While not official Christian doctrine, lynching drew on the idea of “blood sacrifice” central to white evangelical Christianity. As Wilbur Cash observed in his 1941 study of racial violence in the South, “Blood sacrifice is the connection between the purpose of white supremacists, the purity signified in segregation, the magnificence of God’s wrath, and the permission granted the culture through the wrath of ‘justified’ Christians to sacrifice black men on the cross of white solidarity.”

Lynchings regularly followed the model of the tent revival—a raucous fundamentalist Christian church service aesthetically similar to state fairs—with theatrical displays carefully crafted to bridge the gap between the distraction of the physical world and the underlying reality of the spiritual one. Rather than a departure from Christianity, as Douglass had argued, lynchers viewed it as a moral and spiritual duty akin to the framing of Willard and other Christian nationalist reformers.

White Christians employed lynching with greatest frequency in areas with the greatest religious diversity—areas that also had highly segregated churches and neighborhoods. The data suggests that these acts represented assertions of the superiority and power of white churches. Research has also consistently found that white conservatives used lynching as a way of suppressing Black political and economic power, using the spectacle of extreme racist violence to impact not only the victim but the entire community. White Christian nationalists created an unlivable hellscape for their Black neighbors, one that remains visible in Bible Belt communities today.

While Willard’s rhetoric and the Jim Crow state it supported might seem outlandish to some readers, especially those less acquainted with American fundamentalism, it is worth noting the marked similarities of their aims to those of white Christian nationalists of the Republican Party today.

Her frustration that white Northerners “wronged ourselves by putting no safeguard on the ballot-box at the North that would sift out alien illiterates” closely resembles today’s unfounded myths of immigrants voting illegally. Willard’s description of areas with Black voters might easily be quotes from Trump’s comments characterizing Black neighborhoods as “war zones” and rat-infested slums. Likewise, Willard’s assertion that Black voting represented some kind of fraud or trick foisted on real Americans is akin to the lies and conspiracy theories about the 2020 election. But crucially, her pronouncement that a militant, moralizing crusade of Christian nationalists would be the salvation of the nation echoes the most dangerous Christian nationalist rhetoric of the GOP today.

William Horne is a historian of white supremacy and Black liberation at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.