In mid-November of 2023, Helen Toner made what will likely be the most pivotal decision of her career.

Together with three other members of OpenAI’s board, she voted to fire Sam Altman from his role as the company’s CEO. At the time, Toner and her fellow board members were silent about their reasons, saying only that Altman had “not been consistently candid” with them. In the information vacuum, a pressure campaign by Altman’s allies to reinstate him gained momentum. Silicon Valley luminaries, venture capitalists, and OpenAI’s biggest investor, Microsoft, joined the effort—as did most of OpenAI’s employees, whose equity in the company appeared to be at risk of losing most or all of its value. Five days later, Altman was back in the CEO’s chair. Outmaneuvered, Toner and all but one of the other board members who fired Altman agreed to step down.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Toner would later elaborate, alleging that Altman had not informed the board of possible conflicts of interest resulting from his financial ties to OpenAI’s startup fund, had given the board “inaccurate information” about OpenAI’s safety processes, and had lied to other board members in an attempt to push her out. “For years, Sam had made it really difficult for the board to actually do [its] job by withholding information, misrepresenting things that were happening at the company, in some cases outright lying to the board,” she said on a TED podcast in May. (“We do not accept the claims made by Ms. Toner […] regarding events at OpenAI,” two of the company’s new board members, Bret Taylor and Larry Summers, wrote two days later, adding that an independent review found Altman had not acted improperly.)

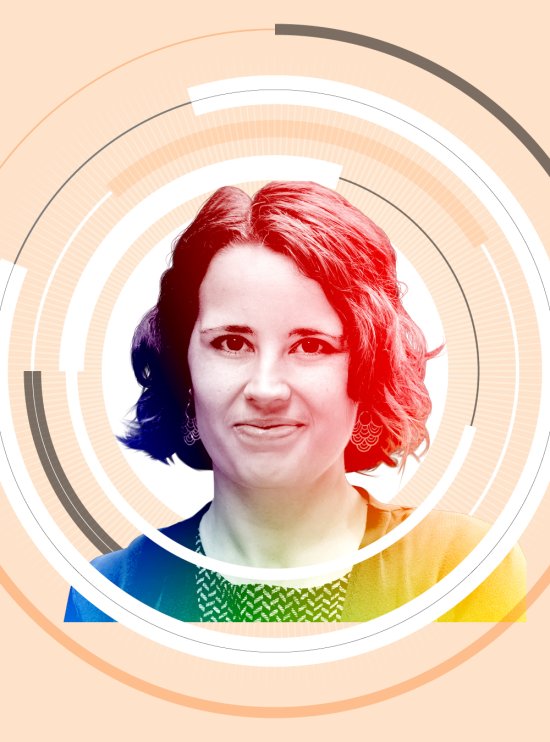

Besides securing Altman’s place at OpenAI, one outcome of the drama was that Toner, a formerly obscure expert in AI governance based at Georgetown University, now has the ear of policymakers around the world trying to regulate AI. She notes that this year, more senior officials have requested her insights than in any previous year.

If she tells those policymakers in private what she has said in public, they’ll hear that self-governance by AI companies doesn’t actually work. Instead, Toner believes governments must step in. “Even with the best of intentions, without external oversight, this kind of self-regulation will end up unenforceable,” she wrote with fellow former OpenAI board member Tasha McCauley in the Economist in May. “Especially under the pressure of immense profit incentives.”

In conversation, Toner is reluctant to discuss OpenAI specifically or the events of last November. Having said her piece, and suffered fierce backlash for it, she is much more at home talking about the nuts and bolts of AI policy, and what it means for politics and national security.

Last year, she says, the public was dazzled by the capabilities of tools like ChatGPT. This year, by contrast, has been one in which we’re increasingly skeptical of letting AI companies write their own rules. Central to this evolution was Altman’s firing, which, although ultimately unsuccessful, pushed AI governance—the question of who should be allowed to make decisions about the increasingly powerful technology—to the fore.

“We’re shifting from a year of initial excitement to a year more of implementation, and coming back to earth, which I think is valuable and productive,” Toner says, leaving unsaid her critical role in that shift. “I’ve noticed a bit more skepticism about just leaving companies to govern themselves.”

Toner says that, even as most companies proclaim to welcome AI regulation, she has also noticed more activity from industry lobbyists advocating against it. This was predictable, she says. As AI regulation turns from something vague and hypothetical into something more tangible, companies are more likely to label unfavorable rules as misguided.

Toner says that her “life’s work” is to consult with lawmakers to help them design AI policy that is sensible and connected to the realities of the technology. But she doesn’t endorse any specific piece of AI legislation. Instead, for now, she prefers that governments around the world try many different things, and stay open to adapting to what works in practice. “The laboratory of democracy has always seemed pretty valuable to me,” she says. “I hope that these different experiments that are being run in how to govern this technology are treated as experiments, and can be adjusted and improved along the way.”

*Disclosure: OpenAI and TIME have a licensing and technology agreement that allows OpenAI to access TIME’s archives.