If the Super Bowl is decided by a field-goal kick, it will look very different from the first time that happened—thanks to European imports with a background in soccer.

Could the Super Bowl be decided by a field goal as time expires?

It’s far from impossible, considering that multiple playoff games this year have already been decided by late missed field goals.

And it’s happened before: a field goal at the end of the game has won the Super Bowl three times in the event’s history.

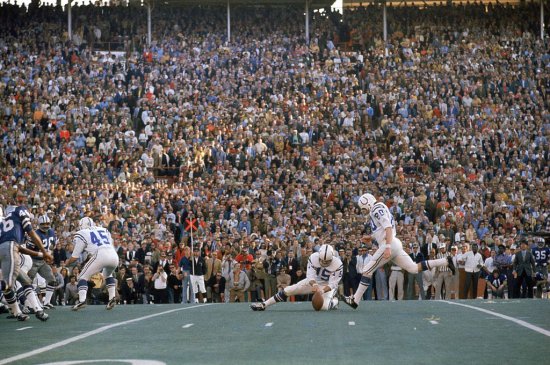

What many fans don’t realize, however, is that field goals have changed over time. When Jim O’Brien of the Baltimore Colts won the 1971 Super Bowl with a 32-yard field goal, it looked very different compared to when Adam Vinatieri won Super Bowls XXXVI and XXXVIII some 30 years later for the New England Patriots. O’Brien used what was then the most common and traditional method of placekicking, in which the kicker took three short steps backwards.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]In 2024, that method of kicking no longer exists and it’s all thanks the influence of European

soccer on the NFL game.

The story of the change in NFL field-goal kicking begins with the aftermath of the 1956

Hungarian Revolution. When the Soviet Union crushed the Hungarian uprising, a 14-year-old named Pete Gogolak and his family fled Budapest for the U.S. Gogolak was a good enough soccer player to have earned a spot on the Hungarian Junior National Team.

Read More: Your Complete Guide to the 2024 Super Bowl: Teams, Tickets, Taylor Swift, and More

Yet when the Gogolaks arrived in Ogdensburg, N.Y., Pete and his brother Charlie were unable to

find a soccer league to play in. So they started playing football. Pete initially played offensive and defensive end. But perhaps not so surprisingly given his soccer prowess, he eventually found his calling as a kicker. He did so using a style very different than the one that kickers had used to that point—one that he adapted from his soccer experience. Gogolak took three steps back and then two to his left before running at the ball as if he were on the soccer pitch.

When Gogolak sent a film of himself kicking 45-yard field goals to the Cornell coaching staff after the 1959 season, they gave him a scholarship. During his three years on the varsity football team (freshman were ineligible), Gogolak made 54 of 55 PATs and still holds the school record for most consecutive conversions, as well as for career conversion percentage.

Gogolak wasn’t the first to use soccer influenced field goal kicking mechanics. In 1957, Polish immigrant Fred Bednarski—whose family had spent three years in a Nazi concentration camp—had kicked that way at the University of Texas. Yet, there is no evidence that Gogolak was aware of Bednarski, so the footwork he used was likely his own invention.

And after his success at Cornell, Gogolak became the first kicker to bring this soccer style to the NFL. Years later he told ESPN’s Doug Williams that a Buffalo Bills scout who had watched him during the spring of 1964 remarked, “Geez, I’ve never seen anybody kick that way.” The Bills of the American Football League drafted him and he made a 57-yarder in his first exhibition against the New York Jets. During his time with the Bills, Gogolak made 47 of his 75 field goals (63%) and converted 76 of 77 extra points.

In 1965, Gogolak jumped to the New York Giants of the NFL, which ignited an “all-out war” between the AFL and the NFL for each other’s talent. Eventually the situation became dire enough that the two competitors merged in 1970. Now playing in the NFL, Gogolak also had the chance to compete against his brother Charlie, who kicked—also using the soccer style—for the then Washington Redskins in 1966. Pete Gogolak would remain with the Giants for nine seasons and today he still holds the team record for scoring with 646 points.

His success sent other teams scrambling to find soccer-style kickers. Many of the kickers they discovered shared backgrounds similar to Gogolak’s. For instance, Garo Yepremian’s family had also fled persecution, in their case the Armenian Genocide. When Yepremian’s brother Krikor was a student at Indiana University, he decided his brother could kick field goals and he wrangled a scholarship offer from Butler University for Garo. But since the Garo had played soccer professionally in Britain, he was ineligible under NCAA regulations. Not deterred, Krikor contacted NFL teams, then negotiated a contract for his brother with the Detroit Lions in 1966.

Yepremian played well for the Lions, and he broke an NFL record by kicking six field goals in one game. But he missed the 1968 and 1969 seasons while serving in the U.S. Army. When he returned, the Lions did not re-sign him since head coach Joe Schmidt thought that “soccer-style kicking is a fad.” Yepremian signed with the Miami Dolphins and helped them win three Super Bowls. For his career, he made 67.1% of his field goals and 95.7% of his conversions.

Yepremian’s success exposed how wrong Schmidt was. Soccer-style kicking was anything but a fad.

The success of Yepremian and Gogolak prompted more foreigners to arrive to try their foot at kicking. Most of them learned the game by coming to the U.S. to play at colleges, but Austrian Toni Fritsch took a more direct route to the NFL. Yugoslavian Bob Kap was coaching the Dallas Tornadoes soccer team and he urged the Cowboys to join the soccer-style revolution. He suggested several players, among them the Austrian star, and Fritsch signed with Dallas. Perhaps his most viral moment came in 1972, when he kicked a behind-the-back onside kick to help the Cowboys beat the San Francisco 49ers.

Read More: America’s Most Popular Sport Belongs to One Person: Patrick Mahomes

The success of these foreign-born kickers helped make soccer-style kicking the norm. And two of the top three scorers in NFL history, Morten Andersen of Denmark and Gary Anderson of South Africa, both of whom debuted in 1982, also were international imports. As soccer’s popularity spread in the U.S., however, the majority of teams reverted to having American kickers.

The ties between soccer and football also may eventually blaze the path for a woman to become a kicker in the NFL. Women’s soccer is incredibly popular and in 1997, Liz Heaston, who was also an honorable mention All–American soccer player, became the first woman to kick an extra point for Willamette University in NCAA Division III. In 2001 and 2003 respectively, Ashley Martin of Jacksonville State University and Katie Hnida of the University of New Mexico were the first women to kick extra points in NCAA Division I–AA and NCAA Division I–A. Also in 2003, Tonya Butler of the University of West Alabama was the first woman to kick a field goal in NCAA Division–II. Several women have kicked soccer-style in high school and college and, in 2010, both Hnida and Julie Harshbarger played professionally in the Continental Indoor Football League.

Women have proved that they can be effective kickers at the high school, collegiate, and even the semi-pro level. One day, an NFL team may also give a woman the chance to demonstrate her skill at that level. In 2019, U.S. National Women’s Team veteran Carli Lloyd visited the Baltimore Ravens training camp and made a 55-yard field goal, hinting at what might be possible.

Over the decades, kicking has improved dramatically, in terms of accuracy and especially the distance from which kickers reliably make field goals. In 2023, the Cowboys Brandon Aubrey made 36 of 38 field goals, including a 60-yard kick. Aubrey came to Dallas from Major League Soccer. Aubrey wasn’t an anomaly either: the Philadelphia Eagles’ Jake Elliott, for example, also made 30 of 32 field goals, and for his career, he’s connected on 86.2% of his tries—a significant improvement over the likes of Yepremian or Gogolak. Both Aubrey and Elliott also made field goals of 60 yards or more, two of five such field goals this year.

Yet, for all of the changes, one thing remains constant: kickers use the style imported by Pete Gogolak, which revolutionized kicking. If Super Bowl LVIII comes down to a kick for either the Kansas City Chiefs’ Harrison Butker or the 49ers Jake Moody, he’ll take the standard three steps back and two steps over before stepping up and booting the ball like a soccer player.

Russ Crawford is a professor of history at Ohio Northern University and a football historian. He has published three books: The Use of Sports to Promote the American Way of Life During the Cold War: Cultural Propaganda, 1945-1963 (2008), Le Football: The History of American Football in France (2016), and Women’s American Football: Breaking Barriers On and Off the Field (2022).

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.