As the U.S., Japan, and South Korea bolster their security ties, experts point to a number of obstacles preventing a NATO-like entity forming anytime soon in Asia.

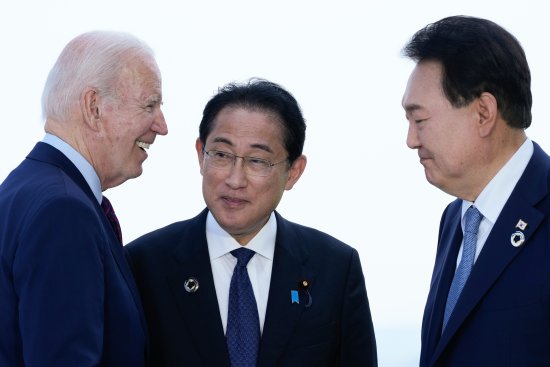

U.S. President Joe Biden will meet at Camp David in Maryland on Friday with his Japanese and South Korean counterparts for a first-of-its-kind trilateral summit aimed at bolstering security partnerships amid increasing tensions in the Asia-Pacific.

The White House said in July that, aside from addressing the “continued threat” of North Korea’s nuclearization, the leaders will use the meeting to focus on how they can fortify relationships with Southeast Asian and Pacific nations to counter China’s increasing exertion and expansion of its influence in the region. The summit is also expected to touch on maintaining peace in the Taiwan Strait. Two senior Biden officials told Reuters earlier this week that the trilateral alliance will launch “joint initiatives on technology and defense,” and a three-way crisis hotline during the meeting.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]The summit is a monumental coming-together for two parties, Japan and South Korea, whose historically strained relationship has been on the mend only in recent months. Some observers have claimed the three-way partnership represents a sort of “mini-NATO,” while others have suggested it could pave the way for a “de facto Asian NATO”—referencing the mutual defense pact formed in 1949 between the U.S., Canada, the U.K., and several European states (since expanding to include almost all of Europe) in response to the security threat posed by the former Soviet Union.

Today, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization is most known for its Article 5, which defines an armed attack on any member state as an attack on the entire coalition—and requires a collective response. It’s an appealing concept for some worried about military aggression from Beijing and Pyongyang. But experts tell TIME that a multilateral, U.S.-led Asian defense alliance like NATO “is not feasible,” nor necessary.

More From TIME

Read More: China Is Testing How Hard It Can Push in the South China Sea Before Someone Pushes Back

The Asia-Pacific is “too diverse politically and economically” to host the formation of a NATO-like construct, Nicholas Szechenyi, deputy director for Asia at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies, tells TIME.

For one, Asian nations are certainly not unified in their opinions on the U.S. and China. The U.S. has found democratic allies in some countries in the Indo-Pacific. But many Southeast Asian states, such as Myanmar and Cambodia, are led by authoritarian regimes, which the U.S. has criticized and China has embraced. Meanwhile, other countries are pursuing strategic non-alignment: India, just behind China in military size with 1.4 million active personnel, has vowed not to side with either the U.S. or China.

But at the core of most states’ expected hesitancy to fully commit to a regional defense pact is economic reliance on China. Analysis by the Economist Intelligence Unit shows China dominates trade in Asia, with every major economy in the region having a bigger two-way goods trade relationship with China than with the U.S. “U.S. allies in the region want to maintain economic interdependence with China but are also uncertain about China’s military ambitions,” says Szechenyi. “This is the dilemma for frontline states.”

Riley Walters, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute specializing in international economics and national security, says a NATO-like construct would be redundant given the existence of other, more specific bilateral and multilateral collective defense arrangements. There’s already the Quad (a security dialogue between Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S.), the ANZUS (Australia-New Zealand-U.S.) Treaty, individual alliances with the Philippines and others, and now the trilateral partnership of the U.S., Japan, and South Korea. “I believe the efforts between the U.S., its allies, and with Taiwan, are already working to deter against [North Korea’s] aggression on the Korean Peninsula and conflict in the Taiwan Strait,” Walters tells TIME.

Walters points to the aid sent by the U.S. and other NATO members to Ukraine, a non-member, as evidence that existing alliances can deter and respond to attacks on third parties. Even the actual NATO, which has stated it sees China as a threat to its interests, is already stepping up its presence in the Asia-Pacific region, with Japan and South Korea having been invited to formal talks with the transatlantic congregation earlier this year. “You don’t need to be a member of NATO to get NATO-like support,” Walters says.