The convention goes back to ancient times, when Roman men were judged harshly for having hair that required extra attention

Do you have a question about history? Send us your question at history@time . com and you might find your answer in a future edition of Now You Know.

Though hair fashions may change season to season, the association between women and long hair is an ancient one.

It dates back at least to ancient Greeks and Romans, and according to archaeologist Elizabeth Bartman, even despite the Ancient Greek ideal of a “bearded, long-haired philosopher,” women in that society still had longer hair than men regularly did. Roman women kept their hair long and tended to part it down the center, and a man devoting too much attention to his hair “risked scorn for appearing effeminate.” The Bible carried on the tradition. Anthony Synnott, a sociologist who has written that hair is a personal symbol with “immense social significance,” found these implications in, for example, St. Paul’s letter to the Corinthians: “Doth not nature itself teach you that if a man have long hair it is a shame unto him? But if a woman have long hair, it is a glory to her.”

“[It is] almost universally culturally found that women have longer hair than men,” says Kurt Stenn, author of Hair: a Human History.

But the reasons why that tradition started out—and why it has endured—are harder to pin down.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

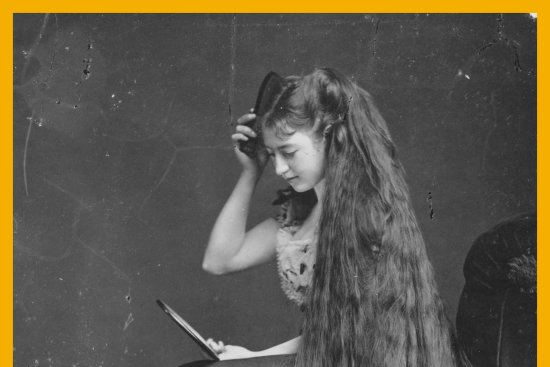

Hair is highly communicative, says Stenn, allowing individuals to send “messages of health, sexuality, religiosity, power” on first glance. It can be an expression of individual and group identity, and the the more attention a person (often a woman) is expected to devote to it, the more it can say. The scholar Deborah Pergament has written that hair’s cultural and historic implications can be legally significant. “Inferences and judgments about a person’s morality, sexual orientation, political persuasion, religious sentiments and, in some cultures, socio-economic status,” she notes, “can sometimes be surmised by seeing a particular hairstyle.”

Stenn, a former professor of pathology and dermatology at Yale who was also the director of skin biology at Johnson & Johnson, believes that health is perhaps the root cause of hair’s significance. “In order to have long hair you have to be healthy,” he says. “You have to eat well, have no diseases, no infectious organisms, you have to have good rest and exercise.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Stenn also notes the practical difficulties of long hair: “In order to have long hair you have to have your needs in life taken care of.” So long hair is also a status symbol, especially when it comes to complex hairstyles that require someone else to help you do them, which “implies you have the wealth to do it.” It’s no coincidence that short hairstyles like the bob came into fashion during the 20th century, in regions where women were beginning to push back against the idea that they needed to be taken care of.

And, the implications of hair go the other way too. Men (especially highborn men, who likewise had the time to care for it) have sometimes worn their hair long, and free Gothic warriors in Italy in the beginning of the last millennium were known as capillati or “long-haired men.” But, in general, their hair was expected to be shorter than the hair of women in their societies. Historian Robert Bartlett has noted that in 1094 “Archbishop Anselm of Canterbury refused to give ashes or his blessing to those young men who ‘grew their hair like girls’ unless they had their hair cut.” Even in the mid-20th century, after women with short hair were less surprising, American men and boys had to fight for the right to grow out their locks.