The policy dates back to 1947

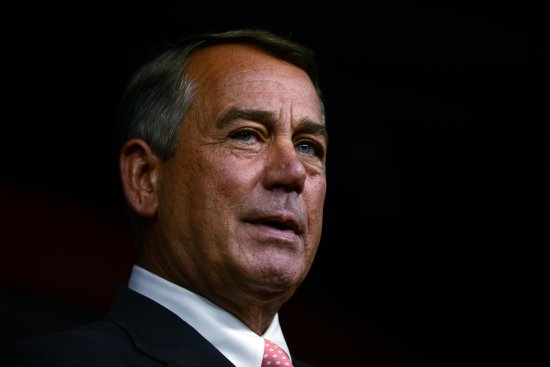

Rep. Kevin McCarthy’s decision this week to drop out of the race for Speaker of the House has left Washington talking about who else might be able to fill that seat. With current Speaker John Boehner leaving office at the end of October, time is running out. But it’s not a choice to be made hastily: the Speaker of the House already wields enormous power in Congress, but he or she also holds even greater potential power. In the event of a President’s death, next in line is Vice President; after that, the Speaker of the House moves to the White House.

But that has not always been the order of succession. In the late 19th century, the protocol specified that after the Vice President, the Senate’s President pro tem would be next in line. That caused a problem in 1881 when President James Garfield was assassinated. His Vice President Chester Allen Arthur was himself seriously ill, but Congress was not in session, so there was no elected officer to be second in line. (Or third, if you count the sitting president as number one.) “As a result of this and other crises,” TIME later reported, “Congress in 1886 passed a new Presidential Succession Act, making the Secretary of State next in line after the Vice President.”

However, in 1945, President Harry Truman requested that the law be changed. He suggested putting the Speaker of the House and then the Senate President pro tem ahead of the Secretary of State. His rationale, as TIME reported, was that the President should not be able to choose his own successor in naming a Secretary of State: “The two Congressional leaders, he said, were more logical successors because they came closest to being elected by all voters of the nation.” Incidentally, Truman’s Secretary of State at the time was quite a young man, while the Congressional leaders were older and more experienced, and thus considered better candidates to run the nation should the need arise.

In 1947, Congress did pass Truman’s suggested law, at which point Speaker Joe Martin, “now just one heartbeat from the White House,” as TIME wrote, “said he hoped President Truman would continue to enjoy ‘the best of health.’”

As TIME pointed out in its coverage, the new law raised a sticky situation for ruling parties that may be even more relevant now than it was in the 1940s: “a Speaker might well be a political opponent of the Administration he would take over.”