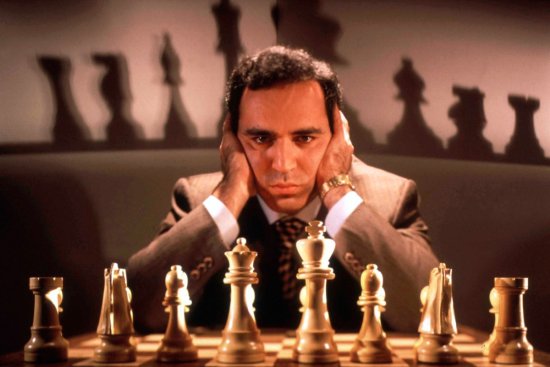

Feb. 17, 1996: Chess champion Garry Kasparov beats the IBM supercomputer “Deep Blue,” winning a six-game chess match

Garry Kasparov was not afraid of a computer. When the world chess champion agreed to play a match against Deep Blue, the IBM supercomputer designed to beat him, he was so confident that, according to TIME, he scoffed at an offer to split the $500,000 purse 60-40 between winner and loser. He preferred all or nothing.

While Kasparov won the match on this day, Feb. 17, in 1996, victory didn’t come as easily as he had predicted. In fact, Deep Blue won the first game they played. It was “a shattering experience” for Kasparov, as his coach told TIME. And he wasn’t the only one reeling. Luddites everywhere were on notice: here was a machine better than humankind’s best at a game that depended as much on gut instinct as sheer calculation. Surely the Cylons were on their way.

But after rallying to beat Deep Blue, winning three matches and drawing two after his initial loss, Kasparov wasn’t ready to give up on the human race — or himself. He later explained, in an essay for TIME, that Deep Blue flummoxed him in that first game by making a move with no immediate material advantage; nudging a pawn into a position where it could be easily captured.

“It was a wonderful and extremely human move,” Kasparov noted, and this apparent humanness threw him for a loop. “I had played a lot of computers but had never experienced anything like this. I could feel — I could smell — a new kind of intelligence across the table.”

Later, he discovered the truth: Deep Blue’s calculation speed was so advanced that, unlike other computers Kasparov had battled before, this one could see the material advantage of losing a pawn even if the advantage came many moves later.

Knowing that it was still basically a calculating machine gave Kasparov his edge back. He boasted, “In the end, that may have been my biggest advantage: I could figure out its priorities and adjust my play. It couldn’t do the same to me. So although I think I did see some signs of intelligence, it’s a weird kind, an inefficient, inflexible kind that makes me think I have a few years left.”

He did not, as it turned out. The next year, he played against a new and improved Deep Blue and lost the match. Once again, the psychological toll of facing off against an inscrutable opponent played a key role. Although he easily won the first game, Deep Blue dominated the second. Kasparov, according to NPR, was visibly perturbed — sighing and rubbing his face — before he abruptly stood and walked away, forfeiting the match.

He later said he was again riled by a move the computer made that was so surprising, so un-machine-like, that he was sure the IBM team had cheated. What it may have been, in fact, was a glitch in Deep Blue’s programming: Faced with too many options and no clear preference, the computer chose a move at random. According to Wired, the move that threw Kasparov off his game and changed the momentum of the match was not a feature, but a bug.

Read TIME’s original analysis of the 1996 face-off, here in the archives: Can Machines Think?